The U.S. spends huge amounts of money on health care that does little or nothing to help patients, and may even harm them. In Colorado, a new analysis shows that the number of tests and treatments conducted for which the risks and costs exceed the benefits has barely budged despite a decade-long attempt to tamp down on such care.

The state βÄî including the government, insurers, and patients themselves βÄî spent $134 million last year on what is called low-value care, according to the report by the , a Denver nonprofit that collects billing data from health plans across Colorado. The top low-value items in terms of spending in each of the past three years were prescriptions for opiates, prescriptions for multiple antipsychotics, and screenings for vitamin D deficiency, according to the analysis.

Nationwide, those treatments raise costs, lead to health complications, and interfere with more appropriate care. But the structure of the U.S. health system, which rewards doctors for providing more care rather than the right care, has made it difficult to stop such waste. Even in places that have reduced or eliminated the financial incentive for additional testing, such as Los Angeles County, low-value care remains a problem.

And when patients are told by physicians or health plans that tests or treatments arenβÄôt needed, they often question whether they are being denied care.

While some highly motivated clinicians have championed effective interventions at their own hospitals or clinics, those efforts have barely moved the needle on low-value care. Of the $3 trillion spent each year on health care in the U.S., 10% to 30% consists of this low-value care, according to multiple estimates.

βÄ€ThereβÄôs a culture of βĉmore is better,βÄôβÄù said , director of the University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design. βÄ€And βĉmore is betterβÄô is very hard to overcome.βÄù

To conduct its study, the Center for Improving Value in Health Care used a calculator developed by Fendrick and others that quantifies spending for services identified as low-value care by the campaign, a collaborative effort of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation and now more than 80 medical specialty societies.

Fendrick said the $134 million tallied in the report represents just βÄ€a small piece of the universe of no- and low-value careβÄù in Colorado. The calculator tracks only the 58 services that developers were most confident reflected low-value care and does not include the costs of the cascade of care that often follows. Every dollar spent on prostate cancer testing in men over 70, for example, results in $6 in follow-up tests and treatments, published in JAMA Network Open in 2022.

In 2013, ChildrenβÄôs Hospital Colorado learned it had the second-highest rate of CT abdominal scans βÄî a low-value service βÄî among U.S. childrenβÄôs hospitals, with about 45% of kids coming to the emergency room with abdominal pain getting the imaging. Research had shown that those scans were not helpful in most cases and exposed the children to unnecessary radiation.

Digging into the problem, clinicians there found that if ER physicians could not find the appendix on an ultrasound, they swiftly ordered a CT scan.

New protocols implemented in 2016 have surgeons come to the ER to evaluate the patient before a CT scan is ordered. The surgeons and emergency doctors can then decide whether the child is at high risk of appendicitis and needs to be admitted, or at low risk and can be sent home. Within two years, the hospital cut its rate of CT scans on children with abdominal pain to 10%, with no increase in complications.

βÄ€One of the hardest things to do in this work is to align financial incentives,βÄù said , an emergency physician at ChildrenβÄôs Colorado who championed the effort, βÄ€because in our health care system, we get paid for what we do.βÄù

Cutting CT scans meant less revenue. But ChildrenβÄôs Colorado worked with an insurance plan to create an incentive program. If the hospital could hold down the rate of high-cost imaging, saving the health plan money, it could earn a bonus from the insurer at the end of the year that would partly offset the lost revenue.

But Bajaj said itβÄôs tough for doctors to deal with patient expectations for testing or treatment. βÄ€ItβÄôs not a great feeling for a parent to come in and I tell them how to support their child through the illness,βÄù Bajaj said. βÄ€They donβÄôt really feel like they got testing done. βĉDid they really evaluate my child?βÄôβÄù

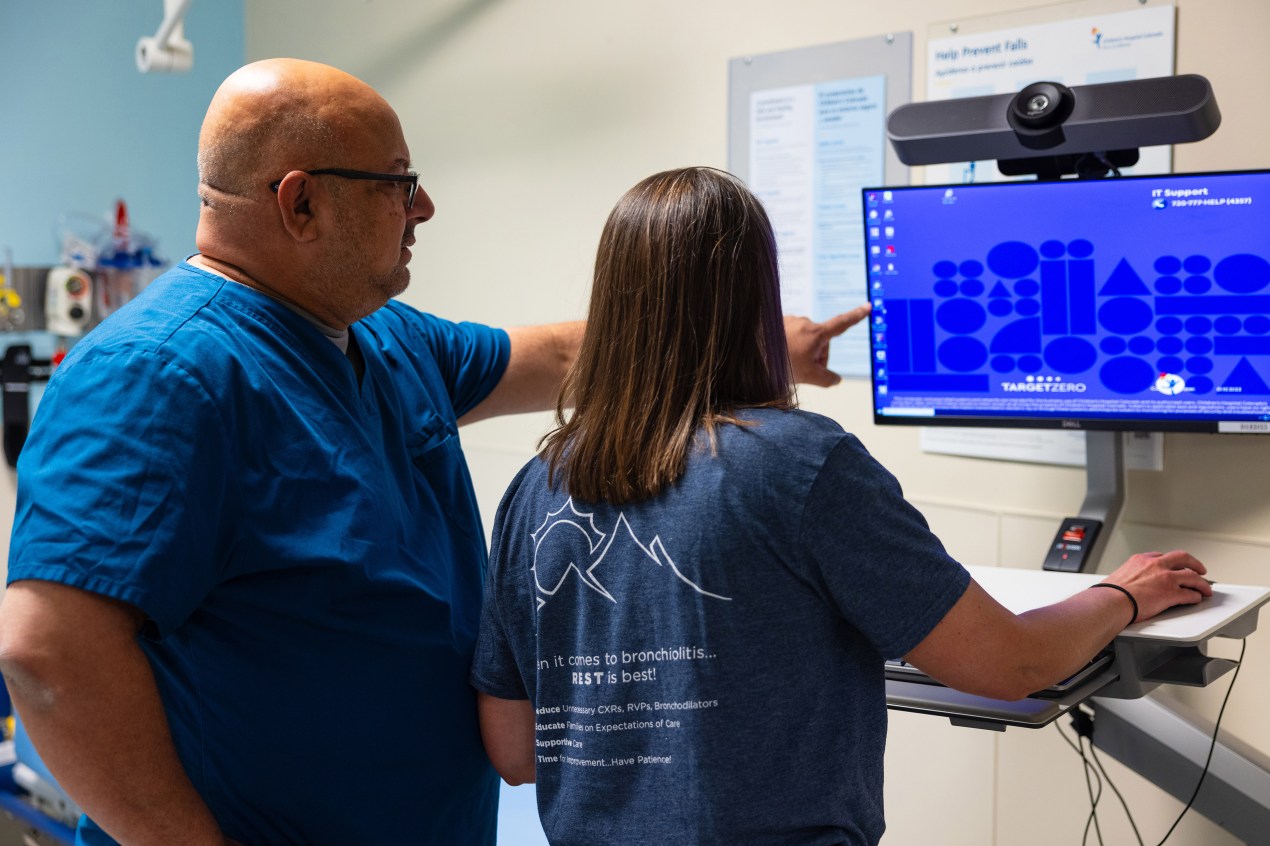

That was a major hurdle in treating kids with bronchiolitis. That respiratory condition, most often caused by a virus, sends thousands of kids every winter to the ER at ChildrenβÄôs, where unneeded chest X-rays were often ordered.

βÄ€The data was telling us that they really didnβÄôt provide any change in care,βÄù Bajaj said. βÄ€What they did was add unnecessary expense.βÄù

Too often, doctors reading the X-rays mistakenly thought they saw a bacterial infection and prescribed antibiotics. They would also prescribe bronchodilators, like albuterol, they thought would help the kids breathe easier. But studies have shown those medicines donβÄôt relieve bronchiolitis.

Bajaj and his colleagues implemented new protocols in 2015 to educate parents on the condition, how to manage symptoms until kids get better, and why imaging or medication is unlikely to help.

βÄ€These are hard concepts for folks,βÄù Bajaj said. Parents want to feel their child has been fully evaluated when they come to the ER, especially since they are often footing more of the bill.

The hospital reduced its X-ray rate from 40% in the 17 months before the new protocols to 29% in the 17 months after implementation, according to Bajaj. The use of bronchodilators dropped from 36% to 22%.

Part of the secret of ChildrenβÄôs success is that they βÄ€brandβÄù their interventions. The hospitalβÄôs quality improvement team gathers staff members from various disciplines to brainstorm ways to reduce low-value care and assign a catchy slogan to the effort: βÄ€Image gentlyβÄù for appendicitis or βÄ€Rest is bestβÄù for bronchiolitis.

βÄ€And then we get T-shirts made. We get mouse pads and water bottles made,βÄù Bajaj said. βÄ€People really do enjoy T-shirts.βÄù

In California, the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, one of the largest safety-net health systems in the country, typically receives a fixed dollar amount for each person it covers regardless of how many services it provides. But the staff found that 90% of patients undergoing cataract surgery were getting extensive preoperative testing, a low-value service. In other health systems, that would normally reflect a do-more-to-get-paid-more scenario.

βÄ€That wasnβÄôt the case here in LA County. Doctors didnβÄôt make more money,βÄù said , an associate professor of medicine at UCLA. βÄ€It suggests that thereβÄôs many other factors other than finances that can be in play.βÄù

As quality improvement staffers at the county health system looked into the reasons, they found the system had instituted a protocol requiring an X-ray, electrocardiograms, and a full set of laboratory tests before the surgery. A records review showed those extra tests werenβÄôt identifying problems that would interfere with an operation, but they did often lead to unnecessary follow-up visits. An anomaly on an EKG might lead to a referral to a cardiologist, and since there was often a backlog of patients waiting for cardiology visits, the surgery could be delayed for months.

In response, the health system developed new guidelines for preoperative screenings and relied on a nurse trained in quality improvement to advise surgeons when preoperative testing was warranted. The initiative drove down the rates of chest X-rays, EKGs, and lab tests by two-thirds, with no increase in adverse events.

lost money in its first year because of high startup costs. But over three years, it resulted in modest savings of about $60,000.

βÄ€A fee-for-service-driven health system where they make more money if they order more tests, they would have lost money,βÄù Mafi said, because they make a profit on each test.

Even though the savings were minimal, patients got needed surgeries faster and did not face a further cascade of unnecessary testing and treatment.

Fendrick said some hospitals make more money providing all those tests in preparation for cataract surgery than they do from the surgeries themselves.

βÄ€These are older people. They get EKGs, they get chest X-rays, and they get bloodwork,βÄù he said. βÄ€Some people need those things, but many donβÄôt.βÄù